the curious case of fiona apple: a lover's epistemology

'if i cannot be loved, let me at least be illegible.'

Her song Parting Gift—Fiona Apple once said—is addressed to ‘all of the men I have known.’ That’s men, plural. It’s a sort of post-love letter for an entire fraternity of jading men. (If I’d written the song, it’d be much longer—there’s the compulsory joke.)

The feeling of the song is posthumous; it is—in many ways—an uncensored eulogy, inelegant but most truthful. Inelegant, I say, because the bitterness is still there. Throughout, Apple refers to these men as her ‘silly, stupid pastime’ that were, all said and done, most fit for inspiring her poetry (‘always good for a rhyme.’) And good for rhyme they are. It’s a brilliant song. The charge that comes at the end of romance, when revelation no longer risks intimacy.

Never Is a Promise, by contrast, is the anterior mode: still in the thick of relation. It is younger, both in terms of when it appears on Fiona’s discography (written nearly a decade prior) and the phase of a relationship it addresses, when the love has not yet waned.

TL;DR If Parting is elegy, Never is flare.

There is a point in putting them side to side. Both songs orbit the same, impossible star: the self-purported opacity of Fiona Apple. Her unknowability, if you will. Especially in love.

In both songs, she says—to lovers past and present—you don’t know me. In one, she says it as verdict, a deep finality. In the other, it’s cast as portent, a forewarning.

Yet she’s saying it.

Fiona resists predictable emotional weather. She’s not the one to go for a banal phrase, never to describe a forest as simply green. What you and I’d call a pretentious jackass, she’d call an ‘orotund mutt’ (which, by the way, the first time I heard it, I thought was an alien species.)

Yet this specific trope, its precise wording, is well-worn—it is the jilted lover’s refrain, the insistence of collegiate grief: you don’t know who I am.

“You never knew me,” says the girl who got stood up, who didn’t get a call back. Says the self-dramatising romantic. I’ve said as much to certain men—one, most recently. I don’t know if it’s true.

“You never knew me,” says the cliché. But if the feeling were more articulate, it might say something like: the offense is not the betrayal of love—it has never been—but the failure of perception.

Even if false, it’s saying something.

We say it often—sarcastically—to friends when they predict exactly who we are. When they gauge exactly what thirty-year-old at the bar we might find attractive and point him out: “you don’t know me!”

To be known is, sometimes, embarrassing.

After the collapse of a romance, Sally Rooney’s young protagonist Frances lays to her side—a half-open copy of Spivak’s Critique of Postcolonial Reason nearby—and thinks of its dense contents soaking up her brain ‘like liquid’: ‘I am going to become so smart no one will understand me.’

It’s a modern scripture: If I cannot be loved, let me at least be illegible.

In a breakup letter of my own, I wrote:

Of course, it had to happen. What else would you expect when someone’s mouth is continuously sewn into myth?

But maybe it wasn’t him. It could have been me trying to retrospectively scribble myself into myth—to coax myself as unintelligible and hieroglyphic in someone’s memory who had, quite simply, left me. Says the girl who got stood up, who got left behind.

I wanted to be the idea that went over someone’s head. I’d always been the idea that went over someone’s head—the straight musician who didn’t like me back, the Hinge date who didn’t reach out after hooking up but, you know, that had only been because I’d talked about Donna Haraway too much. I had self-orphaned myself by studying ideas and icons that were too foreign for my family’s dinner table.

Or, you know, I meant it.

A lover’s epistemology becomes important because knowledge is regarded as the very proof of love.

If this is going to work, he told me at the start of our relationship, I really have to know you.

There’s a story: old mapmakers, lacking proper cloth, polished their lenses with rose petals, leaving behind over time a faint pink haze. Through it, the world gleamed softer, more bearable. A sort of low-budget Instagram filter for the 17th century. By most accounts, the phrase “rose-colored glasses” slipped into the lexicon sometime in the 1840s, already understood as metaphor: to see the world with optimism, sentimentality, a willful distortion. We use it now, often with suspicion. Especially when it comes to love.

Then, going by this logic, the lover’s epistemology—not just in relation to the beloved but in relation to their subjective perception of the entire world—is a wholly unreliable one, obsolete, a madman’s.

“I love everybody,” Mitski sings on Strawberry Blonde, “Because I love you.”

Stendhal—narrowing down—gave it another name: crystallisation. He asked us to imagine it as dropping a bare branch into a salt mine and returning to find it glittering with crystal. The branch is still a branch. What’s changed is the story told about it.

Love, then, is not always about knowing someone, but about an elaborate fiction of seeing. Eros, Anne Carson writes, is in between: the people we love are never just as we desire them.

After a long time of chatting up a new lover to my friends, I finally decide to make them meet. Their sorry faces can’t contain their irreligion: Him? He’s Venus as a boy? Really?

In the diagnostic vocabulary of the Internet, this—this nebulous in between—is called idolisation.

The entire timeline reels, gasps, glitches: Lorde wrote Melodrama about this guy???

Maybe, you think, it is a pathology.

Barthes, in A Lover’s Discourse, resists this flattening. Perhaps it isn’t idolisation, but radical attention. Not seeing falsely, but seeing too much. No one has ever paused to consider this person—this object—with such duration.

Here’s my sentimental hypothesis: that if someone truly regarded a paperclip on a desk—really regarded it—they would fall in love.

Unlike Barthes or Stendhal in their interrogation of how much truth love allows, Fiona isn’t scrutinising—not especially—the truth of her perception of the beloved, but rather his of hers.

In Parting Gift, she opens her eyes when they’re kissing—admittedly ‘more than once’—to study the expression on his face. To dole out the exact shape—canine, sincere—of his affections; what he looks like when he thinks she’s got her eyes closed.

A Peeping Tom in her own bedroom.

I won’t say this is the experience of all women in love, but it has certainly been mine.

So he looks—mid-kiss, eyes-shut—‘as sincere as a dog does’ yet just as the plaintive image is still settling, Fiona disrupts it in the next line by introducing a caveat: when it’s the food on your lips with which he is in love. Then it’s as clear as crystal—not Stendhal’s—that he certainly desires her. Whether he loves her is there for the interpretive taking. But he doesn’t know her and she, after much surreptitious glancing, knows that now.

And it is with this knowledge—of knowing she’s desired, perhaps loved, but not truly seen—that she turns away.

In the second verse, she takes off her glasses when he yells but it is not to stop seeing him, but to stop being seen. Not even his face, but his reading of hers. Anger, sadness—whatever it is that he is misconceiving, she’d rather not know. This is not avoidance—she’s too painfully observant for that—but refusal. I will no longer see myself be misread, even in love.

In a way, the song and its post-haste vantage points—of looking, of watching yourself be looked at, of negating your own perception so as not to see someone’s perception of you and then wishing you had not done so—are a bit disorienting, like a house of smoke and mirrors. But it shows that Fiona has an epistemologist’s graded eye, that she relentlessly inquires the truth of this romance—and thereby her own—through multiple impossible slants.

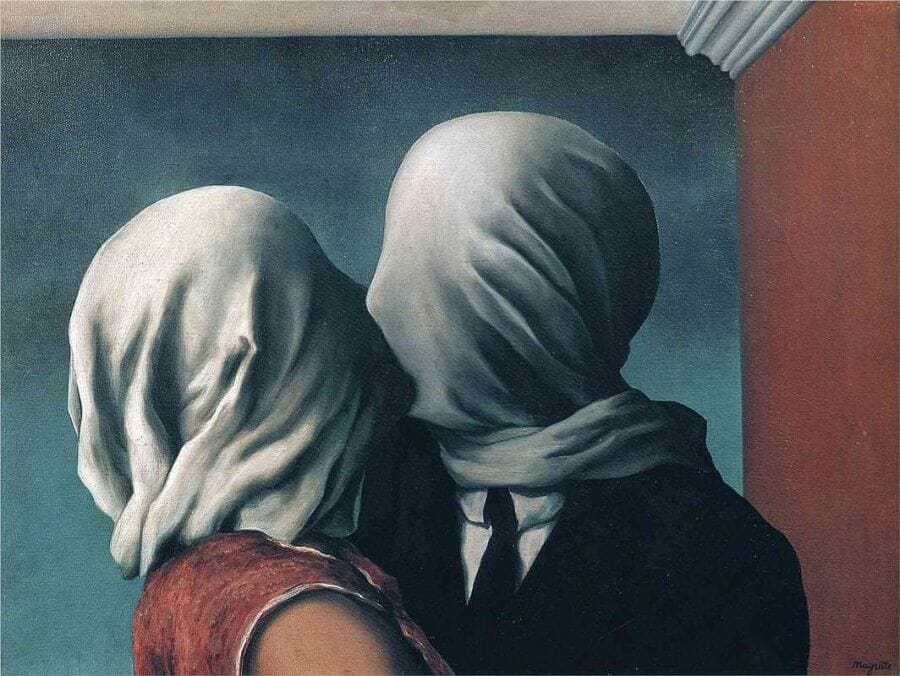

Fiona’s lyrical image—two people kissing to empty ends—reminds me of a Magritte. He called it The Lovers, which reads as either ambitious or bone-dry irony.

Sure enough, two people kiss. But there’s no mouth, no eyes, no warmth of cheek. Only the desperate, childlike press of fabric against fabric. Outside—or what looks like outside—there’s only more flatness, more refusal. It could be sky, or wall, or metaphor. No one says what the weather is.

We are meant to read this as surrealism, but it is not the irrational that unsettles—it is the familiarity. The image could be domestic, even suburban. A bedroom in Westchester. A summer rental in Maine. The cool linens. The ambient grief. It evokes the quiet desolation of an Edward Hopper painting: two figures sharing space but not presence, a couple—perhaps married—long past the threshold of knowing, sealed off by years of accumulated misrecognition.

The achromatic linen clings wetly. It isn’t romantic, maybe erotic. It isn’t even metaphorical, not really. It’s the thing that gets in the way. It’s what we bring with us: shame, memory, misrecognition, a desire not to be seen even as we beg to be understood.

It is—to quote from the recesses of digital folklore—another picture telling us the distance between ‘the rewards of being loved’ and ‘the mortifying ordeal of being known.”

*

In Patricia Lockwood’s post-internet, autofictional work No One is Talking About This, the unnamed narrator—who is reminded of her brother’s ‘guess I’ll die’ memes that she, honestly, never got the appeal of—says to her hairdresser: “I was just thinking that you and I . . . have seen very different memes in our lives.”

A popular meme format that can tell us about the impossible ontological divide in romance is the ‘xyz gf zyx bf’ trend—that is to say, two individuals in a romantic relationship with vastly different hermeneutical footings. The most famous example, and maybe the genesis of this romantic dichotomy, is Barbenheimer. Everyone flocked to tag themselves as either someone that loved pink and “girl-math” or someone monochromatically attired and more mathematically sound.

Yet it soon got progressively more niche, as the internet is wont to do: bf who wears a gold chain gf who is a prominent voice in the menswear community.

It got literary: holden caulfield bf anais nin gf.

And even follicular: bald bf, bush gf.

A variation of this was the xyz gap relationship: age gap relationship (same age but one has instagram brain and the other has twitter brain).

The joke is, or at least was, that the couple’s differences—in temperament and worldview—are comical, even antithetical yet somehow they’re together. The joke is—everyone is unknowable, in love, with each other.

In Never Is a Promise, Apple furnishes a more cynical—and deep-dyed—thesis: that the gap between self and other is not merely wide, but almost mystifyingly irreconcilable. To promise devotion is easy. To know someone is not. The boyfriend (earnest, no doubt) says he’ll stay. But staying is not the same as reaching her.

What can presence offer when the distance is not geographical, not even emotional, but ontological?

“You don’t know who I am,” Fiona tells him.

But, before that: “I don’t know what to believe in.”

The order is crucial.

Before the other fails to know, the self slips from its own grasp.

And yet—and yet. There’s the twist, the paradox. In both songs, Fiona indicts the beloved for not knowing while admitting to expertly having hidden the evidence. In Parting, she concedes the failure was authored by her: “It is my fault, you see / you never learned that much from me.” Later retooled to: “It is by the grace of me/you never learned what I could see.”

Not a lapse, then—a pardon. Grace implies a merciful withholding; it says charity. She’s protecting him against the ruinous, alarmist impulses of her own psychology, her perception troubled by its own depth. She’s seen things, man’s ruinous appetite (or her own), but she’s in no mood to dole it out off the rack—least of all, in some man’s bed. It’s almost a patronising sentiment: you can’t take it.

And what he can’t take is not just the essence of her person, of who she really is, but her uniquely arabesque way of experiencing things—the beautiful, broken grammar of the world as she sees it. Her clarity borders on cruelty. Even side by side with a lover, she already sees him not-seeing her. It’s an almost cruel self-awareness—she sees his ignorance long before he does. On Pale September, she sees her lover ‘unweighted by the intensity or passion’, oblivious to ‘the depth upon which he coasts.’

This is not coquetry, nor feminine mystique. This is not a girl with a fan and a veil. This is hardly the late 18th-century plot of seduction, where a young virtuous heroine is seduced into believing the rake’s vows of love and is ruined when they turn out to be false. She knows. She knows she’s unknown. Her pre-knowledge even takes an erotic dimension in The First Taste, where she sings, ‘I do not struggle in your web/Because it was my aim to get caught.’

Fiona, however, doesn’t plainly despair or even delight in this state of being unknown—at this point, it has little to do with feeling—so much as instrumentalise it. The lover is the audience to a one-woman theatre of control, being led along.

She sees from higher altitudes; he only sees what she allows. It is not that he cannot know—he is not allowed to.

Her knowledge of his not-knowing is its own form of power.

If I cannot be loved, let me at least be illegible.

Kundera, for me, is the true epistemologist of romance in novel form—or, at least, the one to most explicitly gnaw at it. I was assigned Unbearable Lightness of Being in grad school—I’d always had a secondhand copy, gifted by my sister on graduation, that I’d never read—just as I was beginning to fall for a boy. He was much older, almost thirty. A foreign student from Bahrain.

There’s a chapter in Kundera—‘Words Misunderstood’—that is essentially a glossary of mutually misunderstood words between two of its characters, Tomas and Sabina. The words included are sometimes as oddly particular as Sabina’s bowler hat and as elective and open-ended as ‘the beauty of New York’. There is, also, the word cemetery. Sabina sees it as beautiful. The only Czech place she misses. Tomas interprets it as just ‘an ugly dump of stone and bones’.

There is a cemetery near my university—full of British graves from the 1857 rebellion—where I’d taken this man, long before I’d ever gotten to Kundera’s subjective dictionary. It was clear that both of us—like Sabina and Tomas—saw it much differently.

I could tell you what happened that day. I could tell you, for example, the weather was hot in June, though it had rained in the morning. I could tell you that in the cemetery I was blasé and he dewy-eyed, kneeling by a pair of lovers buried together. I could tell you that the fruit of the mulberry tree that hung above us was, for me, bitter. And you might say it was because I could not reach it.

I could explain this interpretive gap between two people as if it mattered. But then it would reveal only an incidental little, if anything at all, about either of them—the man who found a tragic succour in the gravestones and the girl in the prairie skirt for whom the summer wind between them rattled hollow.

Lovers who cannot see each other do not stop wanting.

Magritte’s couple is still kissing their Sisyphean kiss through the veil at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC.

“It ended bad, but I love what we started,” admits Fiona.

In Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil gives us a most useful metaphor:

“Two prisoners whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which separates them but it is also their means of communication. …

Every separation is a link.”

“My baby loves me,” Carrie Brownstein sings in Modern Girl, “I’m so angry.”

So deeply in love, I would listen to this song and cry, for no good reason, on the Metro. The refrain of the song—‘my whole life looks like the picture of a sunny day’—is like an insincere positive affirmation repeated, seemingly, not into a mirror but a moodboard whose idealism you no longer believe in. It is something a Stepford wife might say—asked how she’s doing in the dairy aisle. Anyway, I cried and told no one about it.

Not telling anyone about it, I indulged, makes me a modern girl.

Up the escalators at my arriving metro station, a man waited for me with rare yellow orchids and a smile as insistent and ultimately alienating as Carrie’s refrain.

Yet knowledge is not always occult, ineffable, an evasive abstraction. Sometimes, it’s as simple as knowing how your girlfriend’s period works. Hardly Magritte.

I talk to a lot of people online while writing this essay, mostly women. Madeline, a 26 year old woman from Albuquerque, writes me a DM. She was in the psych ward last week. No spare clothes. Her boyfriend brought her his clothes and a Tom Robbins book he thought she’d like. Her favourite ice cream—Ben and Jerry’s Americone Dream. But, she told me, he doesn’t like to see her when she’s on her period as she is “too difficult to be around”. At most, he’ll bring her food and painkillers at work.

‘The pendulum,’ she says in the DM, ‘swings.’

Nora (she/they)—22 year old queer woman from Ireland, reflecting on a past relationship—tells me: I felt like he knew me externally. ‘He knew all of my interests,’ she says, ‘Even the most niche ones—he would surprise me, for example, with food I mentioned I liked in passing, months earlier.’ Yet, she adds, he never took her politics seriously, although he was left-leaning himself holding views that were ‘maybe even considered more extreme … than me’.

‘He saw my views under an umbrella of feminism/leftist thought,’ they continue, ‘It felt hard to complain about these aspects of our relationship when, in the typically romantic ways, he was a perfect partner.’

Somewhat jokingly, I ask both of these women if they listen to Fiona Apple.

They do.

Everyone says they hate talking stages. I suppose I do too. But I am drawn to the concept: spending an indefinite amount of time getting to know someone—what piece of cinema feels eerily autobiographical to them, their Spotify algorithms, their Bengal cat or how their mother’s orthodontist appointment went. I like the misendeavour of briefly ending up, off target, in the wrong world. I even enjoy the solitary walk back to myself.

The cult of serial monogamy has convinced us that any time spent getting to know someone that’s not meant to be your life partner—your colloquial endgame—is a waste of time. That’s why—halfway through, with premature apprehension—we abandon the project: what’s the use if they’re not the one?

We’re not just bad lovers—we’re bad readers. Which is to say: we don’t want to know each other, we hope to survive each other.

The less I know about you, the less I have to admit you’re not the fantasy.

Call it erotic anti-epistemology.

The dating app profile, like the CV, flattens desire into keywords and categories. Love, in the neoliberal era, has become another domain of managerial efficiency, of hedged bets and preemptive disengagement. In such a landscape, knowing another person—really knowing them—feels almost obscene, too slow for the tempo of the digital.

I’ll admit it: talking to strangers online is nothing like the old, romantic fiction—of, say, Linklater’s Before Sunrise. Mostly, it’s just a lot of pixelated genitalia. Yet we try, remain our prying selves for the next person.

This, Bjork sings on Enjoy, is sex without touching.

Yet she only wants to look—not touch.

Only to smell this—not taste.

I guess this is the dreamily intrusive beginning of most relationships—as if the person were coursework you had to master. It’s foreplay with trivia. To conduct a personal inquiry into each other’s souls and declare—like Brontë’s Cathy—that both yours are made of the same stuff.

Mine certainly went like this.

In a single message, for instance, I was asked—my favourite flower (purple allamandas), my favourite TV show (Twin Peaks), what fictional character I related to the most ‘not in terms of their sense of humour’ (George Costanza), who my closest friend was and, finally, why I wanted to quit smoking (I didn’t.) In turn, I asked him what he thought of the Sally Rooney industrial-complex (he didn’t).

Yet. Yet, on one of our dates outside a historical tomb, I’d wanted to talk to him about something—about why I’d show up drunk on our first and third dates. I wanted to explain to him why romance didn’t seem possible without drinking. ‘I love you and you love me,’ he said. ‘That’s all that matters.’

But I hadn’t finished talking. In fact, I hadn’t even been able to sufficiently preface what I was going to say. But he loves me, I thought.

‘My baby loves me, I’m so angry.’

‘Of course, it had to happen,’ says the breakup letter of the girl who got left behind.

Try as one might, it is impossible to desex this sensibility. The belief is simple, almost homespun: to be known is to be loved. And it recurs—almost pathologically—in the work of women artists. Not as a trope, but as an epistemological demand.

Mitski’s entire discography is a supplication to—not even be truly known, like her white counterparts—but just be seen. In Francis Forever, she can’t stand to be ‘where you don’t see me’. In A Burning Hill, she is both the wildfire and its solitary witness while the lover is ‘not there at all’. In I Bet on Losing Dogs, the closing lines are: ‘someone to watch me die’. In Square, she shakes the hand of a lover: ‘Never once did you know me.’

The woman’s reflection is blanketed, if revealed at all. And when it is revealed, it is revealed only to the lover’s eyes. Burqa, yashmak, ghoonghat—there are, in not that remote places of the world, wedding veils that, once they go up, come down not with the end of ceremony but end of life. The purdah (meaning ‘curtain’) is a form of gender segregation in Muslim, Hindu and Zoroastrian communities that actively hinders women’s participation in public spheres—politics, trade, all sites of mean-making.

White middle-class men, historically, have never required a single gaze to confirm their existence. The man is always-already visible. His reflection flickers in bank windows and barbershop mirrors, in the firm language of utility bills addressed in full. His existence arrives pre-acknowledged. His subjecthood is statistical.

In The Woman in Love, Beauvoir writes:

In most cases she asks her lover first of all for the justification, the exaltation, of her ego . . . The young girl dreamed of herself as seen through men’s eyes, and it is in men’s eyes that the woman believes she has finally found herself.

She quotes then a letter by Katherine Mansfield who, after having bought a ‘ravishing mauve corset’, wrote: Too bad there is no one to see it! In Cosmonauts, Fiona Apple ceases to exist when her lover ‘resists’ her because she only likes the way she looks ‘when looking through your eyes’—the self vanishes if the lover’s gaze is not holding it.

To be known—for a woman—is thus not indulgence. Really, her life is like waiting. A form of seasonal stasis, like rhubarb under snow. The woman is not a flaneuse but a scholar of wallpapers—seen, fully as herself, only in bedrooms. Only by the lover. This has always been a fantasy of being interpreted wholly, correctly just once.

In Me and My Husband (a probable satire of postwar Stepford-wife culture), Mitski is “the idiot with the painted face .. in the corner, taking up space”—but when the door opens, and he (the husband) walks in, she is loved.

Or at the very least: seen.

Someone, finally, to watch her die.

The ever wild, ever queer forest fire, blazing to a merciful witness.

*

I was at a cafe—sipping cold Bailey’s cocktails over delicious Thai grilled whole fish—with one of my best friends and her partner when the subject of caste came up. It was maybe fifteen minutes into the conversation that I realised he didn’t know what caste my friend—who’s a forthcoming Ambedkarite (a school of radical anti-caste thought), by the way—was. I asked him.

‘Oh, you know, one of those,’ he said with a panicky grin.

‘What do you mean—one of those?” my friend said, with a mildly indignant smile because maybe he was joking.

He wasn’t.

He didn’t know.

That was the thing.

He was with her. He had been with her.

And still, he didn’t know.

One might not immediately think The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is about the epistemology of love, though it’s clear. The album begins with Intro—a school bell rings, people settle onto seats, a teacher takes attendance. The word ‘love’ is scratched across the blackboard. Students are asked if they know any media about love and they pitch in: a song called Love by Kirk Franklin, I Will Always Love You by Whitney Houston, Titanic, Romeo and Juliet. ‘Did you know that was about love?’ the teacher says, ‘Or you saw it on TV and they said it was about love?’

Then he asks for a definition of love from one of the guys in class. ‘Let this black man right here tell what his idea of love is,’ he says, ‘Cause not all the time we hear a young black man talk about love.’ He makes sure to tell the young man not to tell the class ‘what Webster thinks’.

‘You think you love someone,’ he says, ‘You should know why you love them, right?’

Yet all of this scholastic speculation on love extends in tandem with the more world-weary landscape of Lauryn Hill’s personal heartbreak. In Intro, when the teacher—taking attendance—calls out Lauryn Hill (at least three times), she’s not there. In the coming songs, it is clear that she, absent from class, has already graduated on to urbanscape where love takes on institutional dimensions. The epistemic insight she recovers is not from the canon—Shakespeare—but from the dog-end of streetwise heartbreak. This is the miseducation of Lauryn Hill. She cuts class and its epistemic violence.

Sadiya Hartman in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments describes waywardness as a ‘practice of possibility’:

Waywardness is an ongoing exploration of what might be; it is an improvisation with the terms of social existence, when the terms have already been dictated, when there is little room to breathe, when you have been sentenced to a life of servitude, when the house of bondage looms in whatever direction you move. It is the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.

Lauryn is brilliantly wayward, literally truant. Likewise, we need to be more than just lovers but romantic delinquents: improvisational, unrepentant and trafficking, as Hartman says, ‘in occult visions of other worlds’.

The album is as much about love—or its slippage—as it is a critique of white capitalist patriarchy. The point is: it is emphatically the same album, inexorable and acute in its marriage of love and its political arithmetic.

‘My emancipation don’t fit your equation,’ Lauryn says to the establishment—or a lover.

Who knows.

Three people—man, woman, man—sit at a hip East Village speakeasy. Yet only two of them seem to talk. We can’t hear them—but the voiceover of another couple on a date amusingly speculates on the relational Venn diagram of the trio. Brother, sister, boyfriend? A couple and their third-wheeler?

This is how Celine Song’s Past Lives opens. It’s a partly autobiographical script about Nora Moon—or Na Young—who, almost after a silver span of twenty five impossible years, finds her childhood sweetheart from Seoul on Facebook. They Skype, they text. Schoolgirlishly. Until, of course, Nora calls it off to focus on her writing career in New York. Then, at a writer’s retreat in Montauk, she meets Arthur and they get hitched. She loves him—they love each other—but she admits that had she met another white man with equal appeal around the same time, she’d have married him to secure a green card. This, then, is the Jane Austen plot for Korean immigrants.

Then, some time later, Hae Sung decides to fly to New York City to meet Nora—no prepubescent strings attached. The film uses the Buddhist-derived concept of inyeon—the idea that the odd happenstance of any two people coming together is the snowballing effect of their thousand past lives—to scale its relationships. At various points, Nora says it to both men. But of course, it’s less other-worldly than that. This world has enough micro-worlds within itself to either divide or draw together the people who hang about it. The film demystifies its own central motif.

Just as Hae Sung is flying to New York City to meet Nora, Arthur—increasingly unsettled by her vague familiarity with Hae Sung—admits: You dream in a language I can’t understand.

Here’s the thing. Nora talks in her sleep. In Korean. There’s a part of Nora—the former component of her Korean American identity—that Arthur just can’t get at. Their marriage is too crowded; a great epistemic failure shares their bed. Arthur could’ve easily been the bad guy. The white man roadblocking a native romance. Except he isn’t. He lets Nora cry in his arms as Hae Sung leaves for the airport.

As for the young lovers, it’s clear that this life is just another one of their past lives—already zooming out, already in sensible retrospect, accommodating not fruition but possibility.

And yet romance must be demythologised. It must go beyond abstraction—skip the lecture on metaphysics—and fulfill itself, most completely, by recognising that the knowingness of a lover is always in deep relation to their distinctive contexts. Not just their abstracted philosophical self, nor their crystallised romantic self, but their material and political self.

This is, partly, what a feminist epistemology of love looks like.

One must know where their girlfriend’s rare dialect comes from, the distinctive edaphology of the soil that raised her, whether she used cutlery growing up—and the why of it all.

Capitalism—through the privatisation of the body, the enclosure of the commons—split love into a two-person project. The neoliberal lover’s insistence for the self to be known exists in a vacuum of Western individualist thought, paying too much attention to the self and not enough to the world around it.

Plato said that one could acquire knowledge of the self by studying the cosmos, or vice versa. This belief is ancient, found in Mesopotamia, ancient Iran as well as Chinese philosophy. What it’s telling us is that knowledge—of the self and consequentially, of another—is always tied to a bigger anchor.

To learn about the world is to thus become a better lover. To remain incurably curious is the basis of a lover’s epistemology.

Mitski’s lyrics—‘I love everybody because I love you’—reprises itself in this light. Love not as rose-colored glasses but as a lifting of the veil.

The act of reading history, then, is always a romantic one.

It was the same friend—from the cafe earlier—who I consulted while writing this essay. Could we be known—in love? Could women be known by a lover while, at the same time, be understood as a lover, as also the subject?

She said she felt known by her lover, mostly. ‘Absolute knowledge,’ she said, ‘would, maybe, be its own sort of violence.’

I agreed. I said I hadn’t ever felt truly seen in love. The closest I came to being pinned down, discovered, was after the relationship had ended. When he offered, as a postscript to our romance, that he felt I’d always loved him as ‘a piece of literature’. It was the muse growing a sudden tongue the truth of which, however partial, I could not deny.

It would not be true to say he didn’t know me at all. We knew each other the way any two people might, had they been us—our exact fragmentary and often laughable selves that specific late November in a leap year when New Delhi was mantled in impossible smog after Diwali. We were always tied to, and gorgeously limited by, the particularity of our own story, our own oblique and nameless epistemologies.

His parting comment—‘a piece of literature’—said another thing. My own gaze could alienate someone. Often enough, we are reciprocally estranging each other and returning, with a sense of righteousness, to our private disquietudes.

It is in her song Werewolf that Fiona finally sidesteps her mythologizing, ‘the habitat of her habits’, and admits her own error. For all her poetry, she finally sees the uselessness of the metaphor. She says she could liken her lover to a lot of things—a werewolf, a shark, a chemical—but, ultimately, she is a ‘sensible’ woman who knows ‘the fiction of the fix’.

The fiction of the fix. The fiction of Stendhal’s salt-encrusted branch. The fiction of Magritte’s The Lovers kissing through mutual veils. The fiction of past lives. The fiction of Lauryn’s classroom, Mitski’s burning hill. And—my favorite—Weil’s fiction of two inmates communicating, with knocks, through a prison wall.

On the internet, someone writes: there’s something beautifully intimate about never speaking to a person again.

Every separation, Weil says, becomes a link.

this was amazing. i sobbed while reading this. thank you so much for writing it. i guess these are scattered thoughts i had for most of my life too, but you made me realize new things, like the neoliberal obsession with the self impedes us from truly knowing each other. I guess that is why I tend to fall in love with people who have curiosity for the world. I still don't know if two people can ever fully know each other, but I have been trying to accept that there are bits and pieces that can resonate strongly with someone, and this piece is one of them. I always felt understood through literature/art, like surely i am not the same person as an author, but it is insane how similar humans emotions/experiences are, and i feel like the logic of everyday conversation does not allow us to do that in the same way other things like art (even eros) does, and this does it for me, it was so beautifully written.

exceptionally well written, not even most published writers write like this! i love how the essay is constructed, the vignettes, the different narrative lenses and absolutely loved the way you dissected Fiona’s songs. “putting language to something for which you have no language is no easy feat” and yet you have managed to do so with such ease. thankyou so much for the wonderful read, this will be on my mind for a long time.